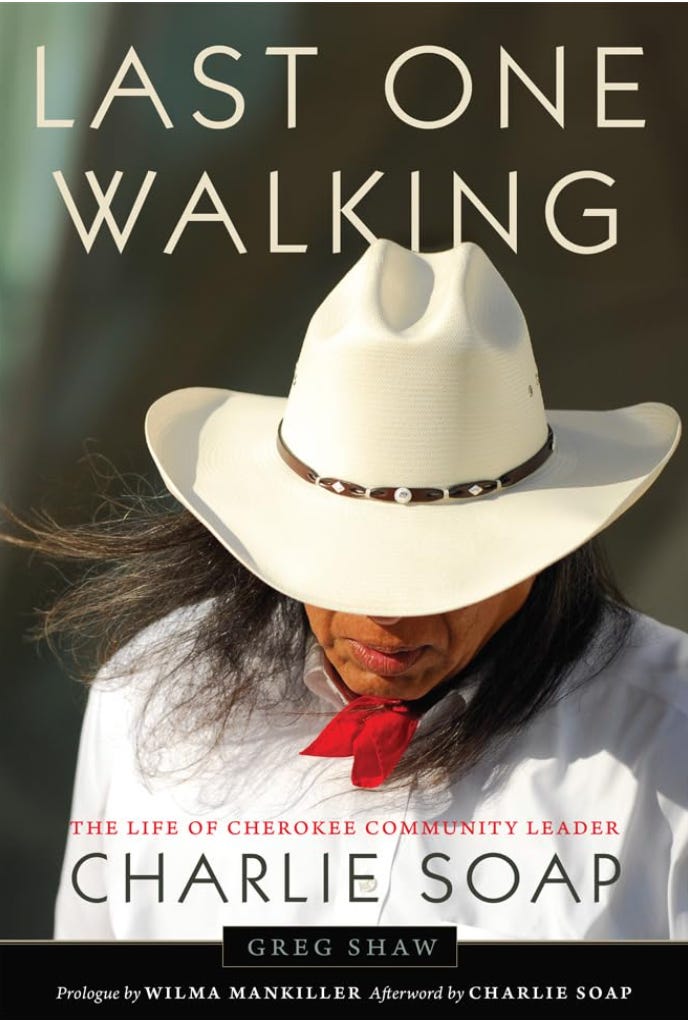

I published Last One Walking (OU Press) in the fall of 2024. It became an Amazon bestseller and was finalist for the Oklahoma Book Award for nonfiction. It is available on Amazon or wherever you buy books.

Preface

The book Charlie and I have written together anticipates two audiences. The first is those already familiar with Native American history and contemporary Indigenous issues. You know the story of Wilma Mankiller, the first woman to serve as principal chief of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. You know it, but you would like to go deeper. The second audience is unfamiliar with this history, but you are curious about leadership, and open to learning more about tribal communities.

For those of you who may have followed Chief Mankiller’s career, this book offers a mostly untold perspective, that of her husband, partner, and the first, First Gentleman of the Cherokee Nation, Charlie Soap. As you will discover, he is consequential in his own right, and he now brings us into his life, and their life together as tribal and community leaders.

For those of you who are new to the story, you will discover an inspiring, brilliant man who is the embodiment of Cherokee history and tradition, someone fully capable of introducing you to his tribe, its values, and challenges. Charlie and Wilma, together, helped Cherokee people help themselves, and to build empathy for poor people by building something tangible – community waterlines and housing.

You may encounter, as you read, terms that are unfamiliar and even uncomfortable. “What is the Trail of Tears?” Or, the author uses Indian, Native American, and Indigenous throughout the book. “Is that, ok?” you might ask. “What about First Peoples and First Nations?” All good questions. For this book, I use the terms that Charlie, and other Cherokee people use. I use them with great humility and respect. For the reader, there is already a robust bookshelf to help answer these questions of identity and identification, and I encourage you to explore it. Perhaps this book will be a launching point.

Charlie asked me to tell his story. I am a white writer who has known poverty personally. I’ve worked with Charlie for 40 years, and I am honored that he asked me. I feel that it is my responsibility to write his story to the best of my ability. To accomplish this, we spent extensive time together in the 1980s, and enjoyed many hours, weeks, and months together in the 2020s in interviews that I recorded digitally or noted by hand.

Our story attempts to cover a lot of ground. The careful reader will notice three distinct and converging voices in the writing that follows – that of Wilma Mankiller, Charlie Soap, and my own, the writer. I have elected to have Wilma and Charlie speak for themselves. I prioritized their words, whenever possible, as they wrote or said them. That is why you will find extensive quotes from their writing and speeches. I felt strongly that Wilma’s opening chapter, which she wrote in her final years, be preserved, largely unedited. Charlie’s stories of experiences during the Vietnam War, his spirituality, and his early engagement with community development, are for him to tell. I have listened, summarized, and consulted Charlie at every step. I did that decades ago during my cub reporting days in the 1980s, and I have continued that tradition in these later years.

The third voice is mine, someone who began as an empathetic young man, and evolved to become a more informed, hopefully wiser man. If the transition between voices is jolting at times, so be it. Sequoyah, creator of the Cherokee written language, described the English documents he saw in the early 1800s as “talking leaves.” Writing paper, or go-we-li ᎪᏪᎵ in Cherokee, is suggestive of a leaf, in Sequoyah’s parlance. In that spirit, Wilma, Charlie, and I are like talking leaves, individual but flowering from and reliant on the same tree.

I took on this project with the greatest respect one person can have for another. My aim is to present the story of a man’s life, a life that is distant to many, yet essential to understanding, or at least beginning to understand, Native American culture. Our story presents Charlie’s family life, his formative years in the US Navy, his spiritual development, and his dedication to serving Cherokee people in some of the poorest communities in America.

Our book profiles my friend, Charlie Soap, and it celebrates the Cherokee principle of Ga-du-gi (ᎦᏚᎩ). Translated from Cherokee, Ga-du-gi means, “collective work for the common good.” Charlie often describes it to mean, “help one another.”

Over centuries it has been a distinguishing characteristic of the Cherokee people. Cherokee and non-Cherokee authors have commented on its meaning. The Finnish historian Pekka Hamalainen writes in Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America that the Cherokees long practiced “a strong communitarian ethos.” He specifically notes that gadugi pervaded the Cherokee world.

Novelist and citizen of the Cherokee Nation, Margaret Verble, and I exchanged emails in 2023 after she published, Stealing, the story of a young Cherokee girl that has been compared with To Kill A Mockingbird. The novel is set within the communities of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, and I asked her if she saw ga-du-gi at work in any of the familial relationships she writes about. “I've always thought ga-du-gi requires a conscious higher purpose, the realization that we're all in this together, and an extension beyond family bonds.”

This book is about Charlie Soap, but it’s also about Ga-du-gi. In the 2013 movie Cherokee Word for Water, the actor Moses Brings Plenty plays the role of Charlie Soap. In one scene, Wilma and Charlie are speaking at a community meeting, one like so many I covered as a reporter for the Cherokee Advocate. We see Charlie trying to articulate why a full-blood Cherokee community, a community that state and county officials had long written off as lazy and hostile, should come together to build a waterline. An old man in the audience speaks up and asks if what Charlie means is Ga-du-Gi. In Cherokee, the intonation of the word can sound like the Cherokee word for bread. Was Charlie describing bread – after all, dinner had been served – or was he speaking about an ancient concept of working together to help everyone?

Charlie responds that he’s not talking about bread, he’s talking about work. This invites chuckles from the closely gathered Cherokees. They understood that the elder was teaching the young Charlie Soap a lesson – the meaning of Ga-du-gi, collective work for the common good.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, the Pottawatomi author of Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants, writes that “generosity is simultaneously a moral and a material imperative.” In her tribe’s language, minidewak means, “they give from the heart.” She reminds us of a Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) pledge of allegiance to gratitude, including this tribute to the many tributaries of water:

“We give thanks to all of the waters of the world for quenching our thirst, for providing strength and nurturing life for all beings. We know its power in many forms: waterfalls and rains, mists and streams, rivers and oceans, snow and ice. We are grateful that the waters are still here and meeting their responsibility to the rest of creation. Can we agree that water is important to our lives and bring our minds together as one to send greetings and thanks to the water? Now our minds are one.”

Like minidewak in Pottawatomi, aloha in Hawaiian, and ubuntu in Swahili, ga-du-gi inspires and informs community action. Ga-du-gi became Charlie’s purpose, and its principle was manifested through community development initiatives designed to bring clean drinking water to underserved populations in the hills of northeastern Oklahoma.

In her book, Making a Difference (OU Press), the first woman to ever head the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, Ada Deer, writes about a meeting held in April 1994 at President Clinton’s White House. The meeting focused on Native American trust lands. She remembers that Wilma presided over this gathering. Wilma had campaigned for Deer during her 1992 run for Congress. Soon after the White House event, Deer adjourned to the Interior Department for a meeting about a water project out west. The first responsibility, she wrote, for the use and management of tribal land, is water rights. In popular culture, the Hollywood film, The Big Short starring Steve Carell, Christian Bale, Ryan Gosling, and Brad Pitt, ends with its hero, Michael Burry, focused on one commodity: water. The author Alex Prud’homme tells the New York Times Book Review that the one subject he wishes more authors would write about is water. “We can survive without oil but not without water.”

For Cherokees, as in many Native cultures, water is not only life, it is sacred. It is healing. It nourishes body and soul. As such, it is not just respected. It is revered. In Cherokee tradition, a-ma a-ti-yi ᎠᎹ ᎠᏘᏱ is a word that conveys both water and the life within it. There, below a spring, river, or well live a-ma a-ti-yi, one or two tiny specimen that ensure the water is safe. As long as they are there, the water will be there. If the a-ma a-ti-yi are not respected, however, they will leave and with them the well will go dry. Disrespect the water by throwing trash in it -- or disrespect it by locating a polluting pipeline nearby -- and a-ma a-ti-yi will leave. And with the departure of the sacred a-ma a-ti-yi, life-giving, soul-nourishing water will go, too.

Last Man Walking is a fascinating, very well written book about Charlie Soap and the Cherokee Nation. I could not put the book down until I was finished. Great work Greg.